"Dear Lord Baby Jesus . . .”

Gathered with his family at the dinner table, NASCAR legend Ricky Bobby is leading his family in prayer, giving thanks for the KFC set before them, when his wife gently interjects, “Hey, um . . . you know, Sweetie, Jesus did grow up. You don’t always have to call him ‘baby.’ It’s a bit odd and off-puttin’ to pray to a baby.”

“Well, look,” Ricky Bobby retorts, “I like the Christmas Jesus best, and I’m sayin’ grace. When you say grace, you can say it to Grown-Up Jesus, or Teenage Jesus, or Bearded Jesus, or whoever you want.”

I know I shouldn’t love this moment as much as I do. But Will Ferrell’s unsophisticated Christology in the 2006 Talladega Nights reveals what is true of many American Christians: we’ve fashioned an entire pantheon of Jesuses to our liking. And the nature of our Jesuses is revealed in the “Christians” they produce. Like Ricky Bobby’s Jesus—“just a little infant, so cuddly, but still omnipotent”—who is being thanked for $21.5 million in annual endorsements.

For Ricky Bobby, for any of us who identify as “Christian,” that’s a pretty safe Jesus to pray to.

So, clearly, there’s been a terrible misunderstanding. No one who ever encountered the real Jesus ever thought of him as a “cherub with a trust fund.”

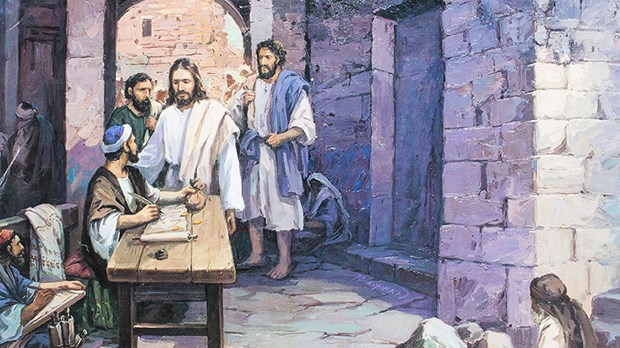

The real Jesus was offensive. Disturbing. He consistently embraced those who were socially, religiously, and legally marginalized. He challenged those who earned the ancient equivalent of $21.5 million annual endorsements. He commanded his followers to die. He called out the religious for their paucity of grace.

There was nothing “safe” about encountering this Jesus.

Pointing to this real Jesus in Teaching a Stone to Talk, Annie Dillard concurs, “Does any-one [sic] have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke?” she demands. “Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets.”

The real Jesus is way more dangerous than NASCAR.

Straw and velvet hats obscuring our view, we too often reduce Jesus to a more manageable version of the one first century Jews and Gentiles knew was not safe at all.

C. S. Lewis also articulates the risk in encountering the real Messiah in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, as four siblings wrestle to understand the nature of his Christ-figure, Aslan. After dinner at Mr. Beaver’s house one evening, Susan discovers that the fabled hero wasn’t a man at all, but a lion. Anxious about meeting him, she wonders aloud whether or not he is safe.

“Safe?” Mr. Beaver clarifies. “Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.”

Upon seeing him clearly, fear was the most appropriate response.

Madeleine L’Engle also identifies that eye-opening moment of discovery: “Suddenly they saw him the way he was, the way he really was all the time,” adding, “We all know that if we really see him we die.”

So we squint. We hide under our floppy hats. Death-resistant, we turn away because we know, instinctively, the risks inherent in being subject to a sovereign whose inaugural address announces:

The Spirit of the LORD is upon me,

for he has anointed me to bring Good News to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim that captives will be released,

that the blind will see,

that the oppressed will be free,

and that the time of the LORD’s favor has come. (Luke 4:18–19)

We intuit enough of what being subject to this king will entail to back away. Instinctively, we dodge people in poverty, avoid prisoners, skirt those with disabilities, and ignore the cries of the oppressed. Tipping our eyes away from the suffering, we choose blindness—and yet, his mission is to open squinty blind eyes like ours.

Throughout the ages those who have recognized the real Jesus—who have seen him clearly and patterned their lives after him—have consistently eschewed safety. People of faith in WWII, like Irena Senler, risked their lives to shelter innocent fugitives. The Rev. George Lee gave his life for the struggle for justice during the American civil rights movement. Archbishop Oscar Romero, moved by Jesus’ love for and commitment to the poor, raised his voice for the oppressed and it cost him his life. Brothers and sisters in South Africa, like Archbishop Desmond Tutu, resisted apartheid in the name of Jesus.

They weren’t safe lives, but they were good.

Shadowing the real Jesus—by living out love for God and people in life and in death—isn’t assigned only to the noteworthy and heroic. It is also meant for those of us who reluctantly fold crumpled laundry, try our best to recycle, and shamelessly throw KFC on our dinner tables. I recognize the contours of the Jesus-life in my neighbor who joins others to sing songs of faith and hope outside the state penitentiary on Christmas morning. I see the recognizable curves in a family that adopts child after child with special needs from foster care. I notice its appearance in a friend whose family has committed to give away all that they earn over what they need.

The shape of a life that is patterned after Jesus is one of sacrificial love for our neighbors.

It’s not at all safe. But it’s good.

Read more articles that highlight writing by Christian women at ChristianityToday.com/Women

Read These Next

Read These Next

What Condoleezza, Hillary, and Deborah Have in CommonKey traits of a compelling leader

What Condoleezza, Hillary, and Deborah Have in CommonKey traits of a compelling leader

The Top 10 Most Popular Articles of 2015Our readers and writers pick the best of TCW.

The Top 10 Most Popular Articles of 2015Our readers and writers pick the best of TCW.

Homepage

Homepage