The False "Help" of Physician-Assisted Suicide

It is so hard to watch a loved one face death in pain and fear, whether it’s for a short amount of time or a years-long battle. Everything within us wants desperately to help them—perhaps at any cost and by any means necessary. But when it comes down to it, what should that help look like, and how far should we go?

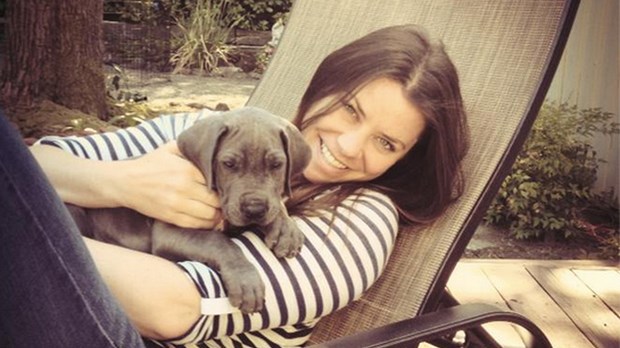

Death is certainly not something we should treat casually. We have to earnestly grapple with what it means to help someone die. And lately, that “help” has taken on a grim face ever since 29-year-old Brittany Maynard took her own life with a “death with dignity prescription” given by her doctor in Oregon. When it became evident Brittany would lose her battle against stage 4 brain cancer, she and her family moved to Oregon, one of the few states that has legalized physician-assisted suicide.

My heart went out to Brittany and her family. No one wants to suffer terrible pain at life’s end. And if doctors are saying you only have a few months to live, why not circumvent the discomfort and choose the timing of your last breath? Why not help her die?

An End to the Suffering?

On an individual basis, what Brittany did seems very appealing. There was a time after the diving accident in which I broke my neck and became a quadriplegic that I wanted to die. I would wrench my head back and forth on my pillow, hoping to break my neck higher and thereby ending my misery. I hated the pain; I loathed the idea of living without use of my hands or legs. So I can understand why people who suffer would want to kill themselves.

But there is more at stake than my suicidal despair or Brittany’s terminal illness—it is not as personal and private a choice as we’d like to think. When you can legally secure a doctor’s help in killing yourself, there are much broader and more dangerous implications. Brittany’s choice has made many others wonder if they should do the same—others whose conditions are not terminal, who are seriously depressed, who are older and not wanting to be a burden to their families. Physician-assisted suicide can send the message that, yes, you might be better off dead than disabled.

The bottom line is people do not want to suffer. Who can blame anyone for that? Living in a wheelchair, having battled stage 3 cancer, and dealing constantly with pain, I can identify. I agree that suffering can feel utterly overwhelming. But people’s fundamental fears about suffering should not be driving social policy. Physician-assisted suicide is bad public policy—the potential for abuse to people with chronic medical conditions far outweighs the small “benefit” provided to relatively few people.

Brittany had a terminal illness. But what does “terminal” mean? What about people with chronic or degenerative diseases? Our broken and profit-driven health care system is already placing undue pressure on people with disabling conditions. Even now, the media is full of calls for reducing “heroic” measures or late-life care in the name of cost containment. With the Affordable Care Act, doctors can be penalized by federal oversight committees that determine whether or not certain health care costs are warranted—in Oregon, insurers have already subtly suggested “death with dignity” as a treatment option.

Personal Rights or the Common Good?

Some would say Brittany has a personal right to privacy that should be respected. But when it comes to personal rights, says, “For we don’t live for ourselves or die for ourselves.” Our choice always impacts others, for the good or the bad. A healthy society will always balance personal rights against the common good of the people. Physician-assisted suicide renders that personal choice tremendously dangerous, undermining the common good by further alienating us from each other, undercutting our sense of compassion, and dismantling our sense of obligation to protect the weak and vulnerable among us.

The responsibility of the state should be to help sick people, not provide for them to kill themselves. There are good laws throughout the U.S. that already help people die with dignity—laws that provide advanced pain management therapies (and even laws that give you the right to refuse treatment).

Do we want to help people die a good death? If fear is the issue, we can surround people with spiritual community and improved hospice care. If intractable pain is the issue, we can funnel more research dollars into better pain management. Compassion is not placing a lethal prescription on a person’s bedside table; compassion is ascribing positive meaning to their condition, lifting them out of social isolation, and giving emotional support. Compassion is also gently helping them explore what may lie ahead for them on the other side of their tombstone.

And this is what saddens me most about Brittany’s death. If I could have parked my wheelchair beside her, I would have wanted to help her see how the love of Jesus has sustained me through chronic pain, quadriplegia, and cancer. I would tenderly warn her about waking up on the other side of eternity only to face a dark, grim existence without God. There is only one person who has transformed the landscape of life-after-death, and that is Jesus, the one who conquered the grave and opened the path to life eternal. A lethal prescription only provided Brittany a quick, temporary reprieve—it is not the answer for the most important passage of her life.

To help someone die is to help them grasp the hope we have in Christ. says, “Christ suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps” (NIV). Just consider all the important things that occurred hours before Jesus died—he ministered to the man dying next to him (), he sorted out family matters (), and he extended mercy to his offenders (). Even the manner in which he died transformed those around him (). A lot of important things happened on Jesus’ “deathbed,” and all of them are examples to us of what it means to die with dignity.

We don’t help dying people by glorifying suffering; we help them by glorifying the God who can be found in the midst of it. Often the gut-wrenching rigors of a terminal illness force you to think about larger-than-life questions concerning eternity—questions most people don’t contemplate when life is comfortable and their health is good. A terminal illness can be an ice-cold splash in the face, waking us up out of our spiritual slumber. It can help us ask: What is life all about? Where am I heading? Have I made my peace with God?

Did Brittany ask herself these questions before she died? Oh, I pray with all my heart she did. I pray she reached out to Jesus before she slipped away, and I pray one day I will see her in heaven.

A Life Worth Suffering For

Sadly, since her passing, so-called death-with-dignity advocates are taking advantage of her death to promote legalization of physician-assisted suicide in more states. But I pray followers of Jesus will resist their efforts. I pray Christians will enter the national debate and create a new narrative, showing people—not just telling, but showing them—that life is worth living, no matter how difficult suffering becomes.

Most of all, I pray you will seriously consider the manner in which you will face your life’s end. Have every confidence that “God, who raised the Lord Jesus, will also raise us with Jesus. . . . That is why we never give up. Though our bodies are dying, our spirits are being renewed every day. For our present troubles are small and won’t last very long. Yet they produce for us a glory that vastly outweighs them and will last forever! So we don’t look at the troubles we can see now; rather, we fix our gaze on things that cannot be seen. For the things we see now will soon be gone, but the things we cannot see will last forever” (). You need not fear suffering. By your courageous response to it, you will be achieving for yourself an eternal glory that far outweighs all your pain and discomfort—it’s what this Bible passage is all about.

says, “You have decided the length of our lives. You know how many months we will live, and we are not given a minute longer.” To help people die before it is their time is not only fatal, it is terribly final. Rather, choose life. Choose the Resurrection and the Life. Choose the Prince of Life, he who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Trust the Word of Life. Choose the Bread of Life and the Breath of Life, and you, too, will see that your last breath is precious—for now, and for all of eternity.

Photo courtesy Zennie Abraham / Flickr

Read more articles that highlight writing by Christian women at ChristianityToday.com/Women

Read These Next

Read These Next

Everyday HeroesMeet six women who are making a difference in our world

Everyday HeroesMeet six women who are making a difference in our world

We Skipped the Honeymoon PhaseWhat I’m learning about gratitude from marrying into motherhood

We Skipped the Honeymoon PhaseWhat I’m learning about gratitude from marrying into motherhood

Homepage

Homepage